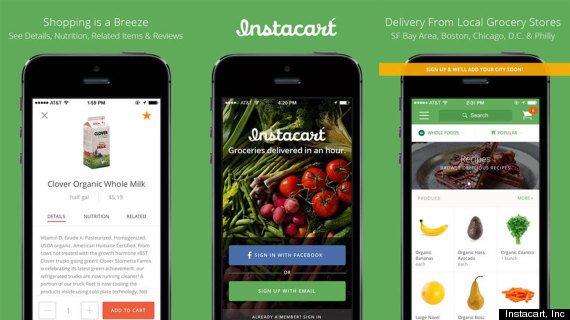

‘Instacart’ App Does Your Boring, Weekend-Ruining Grocery Shopping For You

It’s not the morning commute, the climb to a fifth-floor walkup, or the pressure of being surrounded by the best and the brightest in the world. In New York City, what truly separates the weak from the strong is the weekly trip to the grocery store.

It doesn’t matter if you’re Team Whole Foods, Team Trader Joe’s, or Team I Travel An Hour To The Secret Target in Harlem, grocery shopping often involves being pushed by angry women in yoga pants who will be damned if you get the last bag of kale and standing behind men who just cannot decide which cheese to get.

So when someone else offers to do the grocery shopping for us, we’re quick to jump at the chance to avoid all that hassle. Enter Instacart.

The free iOS app, which got its start in San Francisco and made its NYC debut on March 26, lets customers select grocery items from their local stores. For a $7.99 fee, the order will be delivered within two hours (or at a time of the customer’s choosing).

Grocery delivery services are nothing new. After all, Fresh Direct and Max Delivery have been in the game for awhile now, as have services like Google Shopping Express, the same-day delivery service that has been gaining traction in San Francisco. Instacart offers customers a one-hour delivery option from their local store sans a minimum amount.

Another benefit? A personal touch.

At least that’s what Emma, my Instacart delivery person, told me.

“The difference is that it’s an actual personal shopper just for you,” she said. “Your food isn’t coming out of a warehouse and being put in a box and dropped on your doorstep.”

Having a personal shopper can make a bit of a difference. For example, the food delivered to the office (a bunch of bananas, a mango, and some strawberries) was ready to eat, just as if I had selected it from the grocery store myself. With the app, customers also have the option to select alternate items in case one of their original choices is of stock. (That was the case with that mango you see there.)

While that seems like common sense, anyone who has had groceries delivered can vouch that it’s a risky business. You might open your box to a cracked egg, bruised apple, or smaller-than-expected eggplant.

The entire Instacart process was pleasant. The app is beautifully designed and easy to operate, the delivery was speedy (I ordered at 11:03 a.m., and it was delivered at exactly 12:03 p.m.), and my food was delivered in a cute tote (as opposed to a cardboard box) by a very friendly delivery person.

Here’s a breakdown of what the items I bought from Instacart would cost if they were purchased elsewhere:

These prices reflect the purchase of 5-7 bananas, one mango, and one package of strawberries.

| SERVICE | COST OF PRODUCE | DELIVERY FEE | TOTAL COST |

|---|---|---|---|

| Instacart | $ 13.02 | $ 7.99 | $ 23.01 (tip and tax included) |

| Fresh Direct | $ 9.76 | $ 14.99 + Fuel Surcharge of .68 | $ 25.43 |

| Max Delivery | $ 10.17 | *$ 4.95 | *$ 15.12 |

| Go to the grocery store (Gristedes) | $ 6.67 | – | $ 6.67 |

*Max Delivery has a $20 minimum, so our very small order wouldn’t qualify.

Currently, Instacart is only available to Manhattanites living downtown (below 34th Street and excluding the Financial District), but it has plans to deliver to other neighborhoods in the near future.

“[We are] looking to aggressively expand to the rest of the city and surrounding areas in upcoming weeks as we scale our operations,” an Instacart representative told The Huffington Post.

Instacart also serves areas of Boston, Washington, D.C., Philadelphia and Chicago

Sourced from the huffingtonpost.com

Recent Comments