Working in Retail, Where have all the jobs gone?

When it comes to the business of stocking stuff in rooms with roofs, this has been a nightmare week. Three decades after selling its first personal laptop in 1983, Radio Shack is finally done. The company announced it is filing for bankruptcy just hours after Staples announced its intention to buy the beleaguered Office Depot, which itself merged with OfficeMax. The office-supply chain business is wilting, just as the electronics triumvirate of Circuit City, Radio Shack, and Best Buy has been reduced to one.

The mournful reaction to Radio Shack’s demise is steep with empty nostalgia, and unless you’re a small business owner, the news that there will soon be a solitary brick-and-mortar brand to fulfill your orders for 20,000 Bic pens and 2,000 manila file-folders will not incite much tender weeping. But the incredible shrinking retail chain story is a part of a greater demise that deserves some measure of grief.

It’s not just about the fall of the once mighty paper-pens-and-paper-clips business. It’s not just the national vigil for Radio Shack, summarized lovingly in grainy this-whole-store-fits-in-your-pocket memes:

It’s also the utter collapse of JC Penney. And the trend stories about malls becoming ghost towns. And six consecutive quarters of same-store sales declines at Walmart through 2014. And a deepfreeze among home furnishings companies, and permafrost in dollar-store land.

Retail was the most significant economic industry in the second half of the 1900s. We filled out homes with stuff, and we bought the stuff in stores, made with bricks, filled with people, who were paid to facilitate the transaction.

Since the turn of the century, however, retail employment has been frozen in Carbonite. Real personal consumption expenditures have grown by $1 billion since the recession, and the private sector has added 2.4 million new jobs. But the retail sector has lost 60,000 jobs in that time. Today the stuff that fills our lives is increasingly intangible (college and insurance) or invisible (the Internet and apps).

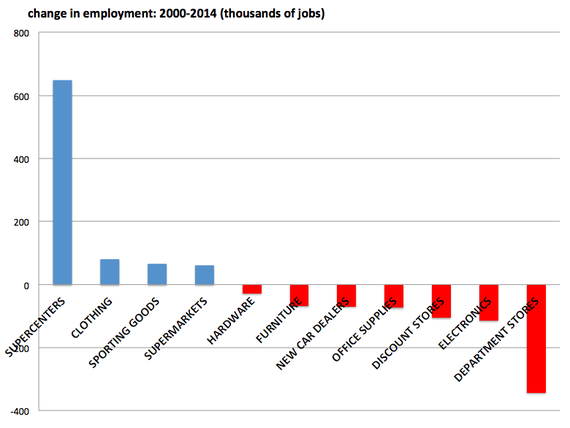

Upon closer examination, though, retail is not suffering an across-the-board chill. Employment at supercenters like Costco and Sam’s Club have grown by 25 percent since the Great Recession started at the end of 2007. But discount stores (like Dollar Tree), clothing-only stores (like Gap), and department stores (like JC Penney) are more than 400,000 jobs lighter than they were when the recession struck. That is the equivalent of about ten weeks of national job creation.

Since 2000, the performance of supercenters and supermarkets has lived up to their first two syllables. But electronics stores and office-supply stores are bleeding red. Job cuts have not been enough to spare Radio Shack and Office Depot.

Costco Up, JC Penney Down: The Retail Jobs Landscape

You don’t need a long explication to see what’s going on here. Walmart brought ruthless efficiency to the business of selling stuff in stores, and Amazon brought more ruthless efficiency to the business of selling stuff anywhere, so that today, to be a retail salesperson or cashier—still the two most common jobs in America—is to compete with the convenience of a laptop and a couch (or, even worse, a smartphone search filling a spare moment of boredom). As Radio Shack’s story shows, when companies go to war against price and convenience, they tend to lose—first go the jobs, then goes the company.

Retail employment is not “dead,” even in the media’s liberal interpretation of the word. Many people love shopping—as an experience—and take more psychic glee from an afternoon out browsing, touching, and bagging merchandise than just about anything in their lives. (And that’s okay!) But as Amazon, eBay, Instacart, and the websites of brick-and-mortar stores primp their digital storefronts, price and convenience will triumph, again and again. There is little reason to think that the most important employment engine of the 20th century will continue to pump through the 21st. The future will be cheap, and it will be convenient, but much of it will lose the personal touch of, well, people.

Sourced from theatlantic.com

Recent Comments