The reality of getting a promotion at Walmart

This Walmart worker went from temp to store manager. Here’s why that’s so tough.

A few days ago, the National Retail Federation posted a video on its Web site sketching out the career of Claudine McKenzie, a manager of a Walmart in Sunrise, Fla. It’s an inspirational tale: The daughter of poor Caribbean immigrants started out as a temporary worker when she was 20 years old and three months pregnant. Over the next 17 years, she had two kids, put herself through college and a master’s degree program, and worked her way up to a six-figure salary. After McKenzie went on television to advertise that her store was hiring temp workers for the holidays, the NRF reached out to see if she’d want to tell her life story on her employer’s behalf.

The video is only 2½ minutes long, which leaves out a lot. Contacted by phone, McKenzie filled in the gaps, by way of explaining why all Walmart associates can advance themselves too.

“People need to know the other side of the story, with all the negative things in the news,” she said in an interview. “We don’t publicize the good things. People see the bad things, and they don’t apply. When we don’t publicize these things, we’re actually taking away some of these opportunities. They won’t apply, and start out, and be the next store manager, and be the next me.”

It may be true that anyone with McKenzie’s gumption and drive can get ahead — and even that many Walmart associates do the same. But there are also structural reasons why most Americans don’t. Let’s walk through her story and see how representative it is of the country at large (the quotes are a mix of the video transcript and an interview).

“I started Walmart 17 years ago as a sales clerk in Miramar, Florida. I was 3 months pregnant with my son. I had no idea what I would do for a source of income. At the time I was enrolled in school, needed to get a job and care for my son. I moved on to department manager in boys, infants, and girls. When I went out to have my son, Walmart provided insurance and short-term disability. It was amazing, the support that I had from the company.”

The remarkable Ms. McKenzie. (LinkedIn)

How easy is it to have a kid as an hourly Walmart associate? According to a spokesman, the company offers a program called “Life with Baby,” which is “an initiative designed to give associates and their spouses personalized tools and education to help them have healthier pregnancies and infants.” As far as maternity leave, you can only get it if you bought disability insurance, which McKenzie did because she knew she would soon have a baby. Salaried employees get 90 days of maternity leave, and new fathers get 14 days of paternity leave. Nationwide, the situation is similar: Only 11 percent of private-sector workers have access to paid parental leave.

McKenzie’s story is also remarkable because she was a single mom, with no partner to support her child, though her mother moved down from New Jersey to take care of McKenzie’s first son while she worked. She started out at minimum wage of $5.75 an hour, got $7.95 an hour as a supervisor, $9 as a department manager, and a base annual salary of $35,000 as an assistant manager. Despite having to support a family on a very low income, she says she didn’t take any form of public assistance. But lots of her colleagues do: In many states, Walmart tends to be the employer with the most workers receiving Medicaid and food stamps. That’s largely because of its size; dollar stores and fast-food restaurants often have a higher proportion of their employees on public assistance. Still, rock-bottom wages make it difficult to pass up government help.

Now, as a store manager, she’s doing really well.

“When you think of doctors and lawyers, that’s what we make. Six figures.”

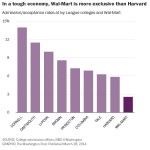

That’s actually rare. According to a salary analysis from the career Web site Bright.com, only 10 percent of people with Walmart on their résumés ever make more than $70,000 a year, which is not the worst of all companies, but is still low. But McKenzie says everybody can move on up if they work hard enough.

“The thing is, working for Walmart is what you make of it. If you want it, there is so much growth in the company. People who don’t grow at Walmart, it’s because they’re comfortable in their jobs, and they don’t want to go further. The people who complain the most are the ones who are not going after what they truly want. You can’t sit back and ask for something unless you’ve really earned it. If you want more money, then apply for more money when jobs open up. …When nobody else wanted to do something, I said, ‘I’ll do it!’ Every time there was an extra day, I said, ‘I’ll work it!’ Oh, my god, they would have to send me home, because I would volunteer for everything. They’re a large company — there’s always something for everyone to do; people just don’t want to do it.”

Can everyone truly just get a better-paying job within the company if they’re unhappy making minimum wage? Walmart says it promotes 160,000 associates each year and that 75 percent of its managers started out as hourly employees. That’s laudable. But, at the same time, not everybody can get promoted to a job that makes a middle-class salary. For example, there are only eight assistant managers per store, with a base salary of $35,000; plus four shift managers and one store manager, who make more. That comes out to about 62,500 positions, or less than five percent of the company’s 1.3 million associates. There are obviously other positions along the Walmart supply chain, but here’s the point: The pyramid has a very broad base, and if all associates are inherently competing with one another for better-paid positions, some of them won’t get far.

So, what about those who do still make the minimum wage?

“If the federal minimum wage goes up, our company doesn’t have a problem complying with it. If it goes up, we go up. And with the increase in a minimum wage, you retain good people. The higher people get paid, the more satisfied they are. But you have to look at Walmart’s overall benefits. If you add all that up, the compensation far exceeds most employers out there.”

That’s a significant admission in itself — the National Retail Federation, which made the video, staunchly opposes raising the minimum wage. As for the claim that benefits make up for it, Walmart’s package does offer some advantages, like a six percent 401(k) match and an array of health-care coverage options (here’s a PDF summary). But the company says only that “more than half” of associates are enrolled in the plan, which doesn’t come anywhere close to industry-leading Costco. CNN suggested that many Walmart associates can’t afford it.

Then there’s the female empowerment message.

“One of the things I love as a store manager is the influence I have on other young ladies. As a minority female, I serve as an inspiration to other minority females. My story shows that they have the ability to be whatever they want.”

It’s worth remembering the class-action lawsuit filed against Walmart for gender-based discrimination in promotions. Though the suit was ultimately thrown out, that’s 150,000 people who disagreed with McKenzie enough to put their names on a legal filing.

Now, how about education?

“The company’s enabled me to go back to school. I currently have a bachelor’s degree and am working on my master’s. Walmart has supported me and given me all of that….it wasn’t that I had to, because at this point I was making really good money. But I decided that going back to school was a personal accomplishment of mine. And I took one class at a time.”

The company offers tuition assistance for classes at American Public University, an accredited, for-profit, online-only college, as well scholarships for other institutions. McKenzie picked American Intercontinental University, and paid her own tuition while working. That’s also great — but don’t forget that income inequality and racial disparities are still huge drivers of educational inequity, which is part of the reason why not everybody transcends their station.

McKenzie also defended the company’s enduring resistance to union organizing.

“I don’t think our associates should have to go to an outside source to speak for them. I should be able to speak for me and get the same result. We’re not against anything, but we feel like our associates have the right to speak for themselves.”

Earlier this month, the National Labor Relations Board charged Walmart with retaliating against some of the workers who went on strike in 100 cities across the country before the holidays. It appears that quite a few workers don’t feel like their individual voices are being heard.

To be sure, McKenzie beat the odds. That’s wonderful, and it’s fair for Walmart associates to take inspiration from her example. But it’s not proof that all our ladders to opportunity, as the White House calls them, are all in good working order. The United States still has an economic mobility problem, after all — and it’s worst in the areas where Walmart’s presence is most felt.

Where the Walmarts are. (Excelhero.com)

Where people are most and least economically mobile. (http://www.equality-of-opportunity.org/)

Sourced from Washingtonpost.com

More From I Hate Working in Retail

Share the joy

Recent Comments